1968-78 was a period of convergence between the old and the new generations of activists in the Chinese, Filipino, and Japanese communities. A new common cause developed between the two generations, one in their elderly years, the other youths coming of age. The older generations were veterans of past struggles. In their youth during the 1920’s they had faced exclusion laws and anti-Asian racism. In the 1930’s they fought against hunger and unemployment during America’s severe economic depression. Filipino, Japanese and Chinese workers fought to unionize the low wage industries alongside their fellow American workers. In World War II, Chinese, Filipino, and Japanese Americans served in the American military, while Japanese Americans were forcibly interned in concentration camps. And during the 1950’s Korean War and the U.S. Cold War against China and the Soviet Union, the Chinese American immigrants were persecuted by the McCarthy confession program, facing deportations and denial of citizenship rights. By 1968, the old left found new hope in the youthful Asian Americans coming back to the community.

The Asian American new left emerged from the TWLF strikes in the surrounding Bay Area campuses. Seeking guidance in community politics, the young activists sought and received support from the revitalized old left. Chinese, Japanese and Filipino student activists within Chinatown, Manilatown and Japantown found generational contacts with the old left. Asian American pan-ethnic politics had to adapt to new conditions that were much more ethnic-specific. As political organizing focused on specific ethnic communities, there were new tensions that challenged the validity of Asian American pan-ethnicity. At the same time, young Asian American activists established valuable working relationships with older community members whose experiences dated back to the pre-World War II period.

Although the old and new left had vastly different experiences, the rise of a new social movement in America created conditions for the elderly and youthful activists to form a solidarity that dramatically weakened the grip of conservative politics in their communities. With this new solidarity, a progressive voice emerged, successfully challenging a conservative political structure that had seriously hampered the political freedoms in the Asian American communities. The results were nothing short of a political awakening that helped bridge the gap between the earlier movements of the 1930's, 40's and the new activism of the late 1960's and 70's. This inter-generational merger provided an important contribution to the maturation of Asian American activism.

Chinatown “Home Country” Politics and the Asian American Movement

In Chinatown the politics of the old left was essentially home country nationalism. Its goals were to free the Chinese ancestral home country from the shackles of colonialism and feudalism. Their nationalism stemmed from the colonial experience in China and their experience as a racially excluded minority in the U.S. In addition, many Chinatown old left had been active in the American labor movement and also saw themselves as part of an international working class movement. Other Chinatown old left progressives who were non-workers; including students, professionals and business entrepreneurs, saw support for China as part of the overall responsibility of overseas Chinese. Their nationalism was also fueled by racial exclusion in the U.S. During World War II, these older ‘left’ forces conducted numerous fundraising and other support functions to defend China against Japanese militarism and later to support the newly established People’s Republic of China (PRC). These campaigns instilled within the old left the belief that they were overseas Chinese and “home” was on both shores of the Pacific.

The old left also believed in integration into mainstream institutions in America, including labor unions and other professions. They formed organizations in the 1920’s, such as Min Qing (MQ, a Chinese student club); Chinese Workers Mutual Aid Association (CWMAA); and Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance (CHLA), which encouraged their membership to work for democracy in China as well as for Chinese Americans in America. The organizations provided self-help services for immigrant newcomers, social and cultural functions for youth, writing clubs, music clubs and employment searches.

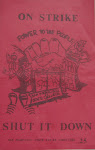

Following are excerpts from the Wei Min newspaper written by or about the experiences of this older generation of Chinatown activists.

No comments:

Post a Comment