Shortly after the period of organizing students to struggle for the establishment of various Asian American Studies programs on the college campuses, the activism naturally spilled over into the surrounding communities. This took the form of establishing community centers and organizations that focussed on “serve the people” programs. In the San Francisco Bay Area, Asian American activism found its new direction in the opening of a number centers. In San Francisco, this included the Asian Community Center, Asian Legal Services, Chinese Progressive Association, International Hotel Tenants Association, Japanese Community Youth Center, J-Town Collective and Kearny Street Workshop. In the East Bay, East Bay Asians For Community Action and Berkeley Asian Community Center provided avenues for the community to utilize its centers to organize around community needs. Similarly, in New York Chinatown, the Basement Workshop was established that provided space for community media projects. In one evening, 2,000 posters were silk-screened for use in a police brutality demonstration at City Hall. ESL, citizenship and youth programs were held at the Basement Workshop.

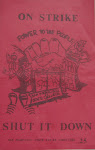

Much different from campus, community activism had to speak to the local needs and conditions of the Asian American community. Insofar as the movement was grounded in local conditions; grassroots leadership and participation was realized. The Asian Community Center became a focal point of local activism in 1974 when Jung Sai garment and Lee Mah Electronic workers used the location for community strike support activities. In 1971, the Chinese American community utilized both Asian Community Center and Chinese Progressive Association to organize welcoming activities for the visit by the Chinese Ping Pong Delegation to the US. For over two decades, the longing of community residents for improved US-China relations had been suppressed by US Cold War politics and control of the Chinese American community by the Kuomintang Party (KMT) that was based in Taiwan. Locations such as the ACC and CPA provided political space in which this imbalance was radically altered.

Another mobilizing point for Asian American movement was the struggle against the eviction of the International Hotel tenants in San Francisco. The International Hotel began as a local fight between a local developer and mostly Filipino and Chinese residents living within the Manilatown area. But within this local background were multiple levels of power that represented globalization—in the form of Bay Area Regional master plans, Pacific Rim development and Asian finance capital. These forces had already destroyed most of Manilatown and were eliminating many existing housing units the adjoining Chinatown (mostly bachelor hotel rooms), replacing them with office highrise buildings.

Similarly, redevelopment-related issues were focal points of protest in other Asian American communities. In 1973, SF Japantown, the Committee Against Nihonmachi Evictions (CANE), consisting of the J-Town Collective and community individuals, emerged to address the needs of residents and small businesses. CANE became involved in supporting low-income affordable housing issues and protests against destruction of residential and small business districts. It had a membership base of over 300 residents who were discontented over direction of redevelopment largely owned by Japanese multinational corporations.

No comments:

Post a Comment