a better garment factory

The

Wei Min Chinese Community News. Vol 1, No. 1. October 1971. P. 3.

The Chinatown Cooperative garment factory--humming machines, laughing, talking voices. At first it looks like the other garment factories in

At the Chinatown Cooperative, there is no boss. The Co-op is run and controlled by its workers. Together the workers decide what work they will do, time they will put in, and discuss the financial situation of the Co-op. When the manufacturers come in with contract work, the workers negotiate with them for the prices. They plan their own lines of clothes and arrange for the cutters and materials themselves. What brought these Chinese and Filipino women together to start their own business? Why did they pick this way of operation?

GOOD ALTERNATIVE

To the women of the Co-op, the factory is their alternative to the exploitative work conditions that face garment workers in other factories. It means a step to self-pride, reap the benefits of their labor, and eliminating the middle man or contractor who decides the pay and work conditions of the workers.

Much has been learned about the competitive nature of the garment industry and the myth that the

Right now about 3500 women are employed in

THE WHOLE PICTURE

The Transitory nature of fashion dictates that the apparel industry

stay away from large-scale methods of production. Instead it relies on small-scale methods of production: the small size of factories and manufacturers, the separation of functions in production, and seasonal changes. The only factories which employ several hundred workers are those which produce cheap merchandise in large quantities like Levi Strauss.

The different functions of production can be seen as divided by profit levels. The manufacturer is the one who gets the materials and determines the what, when, and. where of production. He could do all the production. in his own plant, but instead he gets the materials, does the cutting, and than contracts it out for physical production. This way he is relieved of managerial decisions pertaining to labor and work conditions.

The contractor is at the next level. He bids for work from the manufacturer and receives a certain amount for the production of the garments. The labor and management of the shop are his concern. Entry into contracting business requires little capital. The result is a large number of contractors competing among themselves. This gives the manufacturer the option to offer whatever price he wants for the work. If one contractor doesn’t take it at his price, another will. In

The contractor, in order to successfully compete for work, tries to decrease his labor costs. Wages are lowered and hours increased for workers. Piece-work is used in order to increase the workers’ production and not their wages.

The Chinatown Co-op is not the first time garment workers in

But when the garment workers became predominantly women in the 1900’s, the guilds began to lose their strength. Immigration and language pressures limited the women’s capabilities in fighting for higher wages. The guilds soon disappeared.

The union that is now trying to organize in

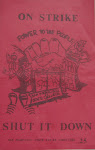

The Chinatown Cooperative is a new alternative for garment workers. Not only is it the first business in

No comments:

Post a Comment