When my son was one year old, a brother from the Chinatown Cooperative Garment Factory came to visit me in my Berkeley apartment and asked me to volunteer. The alternative garment factory was located in the basement of the International Hotel in San Francisco. I had dropped out of UC Berkeley when I became pregnant in my freshman year, and I guess he thought I had plenty of time??

I decided to check it out and went down to the Asian Community Center where the Garment Co-op had a space.

The Asian Community Center was familiar territory for me. In my freshman year, while working as an office assistant for the UCB Asian American Studies Department, we students had temporarily moved the AAS office into a field office inside ACC to help out community fieldwork. ACC offered Chinatown a free food program, community film showings, youth program, and labor support. We used to call Kearny Street where ACC was located, “The Block”. A number of community organizations rented the retail and basement spaces below the tenant-controlled International Hotel. It was like Asians had seized this block, the way Native Americans had seized Alcatraz Island.

I had never been inside the Garment Co-op before. You had to enter through a dark unlit foyer. Behind its darkened closed door you could hear the whirl of sewing machines. I knocked and the door opened into a brightly lit room. Six women were chatting while they worked, and looked up at me from their machines. Vicci wearing an apron and her hair tied in a bandana let me in. Mrs. Lum, the co-op worker, stood up and warmly greeted me in Cantonese. I couldn’t speak or understand Chinese, so I didn’t do much but say hello. I could guess Vicci was thinking, oh no, another empty-headed student. The Co-op was run by the immigrant women workers, with no bosses. They were paid hourly wages, unlike the piece-rate sweatshops in Chinatown. The workers had full control of production and working conditions. Every day during break, they had English lessons, exercise, and current events classes. A few times a year, the Co-op had family picnics for recreation. The Co-op workers enjoyed working with the young people from ACC. They even gave friendly nicknames for some of the ACC volunteers. There was Shrimp Boy, and the three stooges; Stooge One, Stooge Two, and Stooge Three.

It was a new experience for me to watch these working class women laugh and joke around while they pushed the cloth pieces through the rapidly pounding needles. Don’t they worry about their fingers? These women could deftly sew scores of pieces in a non stop string, scissors flying as they rip the connecting threads, tie the sewn pieces together into a bundle, and pass it on to the next operator without missing a beat. They taught me to operate the machines and watch over my quality of work. Without a doubt they took pride in their production. Their conversations were filled with their life difficulties trying to make financial ends meet, trying to find jobs that paid a living wage, worrying about their families whom they loved so much that they’d work long overtime hours to finish the contracts, extending the workweek into the weekend. Work on Saturdays? Not me. Until I understood how much they relied on one another. If I didn’t help on extended hours then the next operation would not have enough work and would have to go home.

I took this experience with me to every garment factory I worked in for the next five years. Every factory was the same in the camaraderie of the women, working in teams and sections, with the factories as large as 100 to 300 workers. And I brought with me the fighting spirit of the co-op women. When the contractors tried to force low price rates on their work, the co-op workers would plan a group confrontation. Then when the contractor came into the factory, he was met by a united group of women demanding a fair price per garment from the manufacturer. At each factory since, I encouraged similar cooperation in fighting for better working conditions.

Without exception, someone would always complain I was a communist, and then give me a lecture on how communists in China confiscated their family wealth. After arguing this point, the logic of uniting eventually banded people together as a group to take action and confront their supervisor for fairer rates. Their small victories encouraged others to do likewise. I was deeply respectful for these women who risked being fired by taking action and grateful for their patience enduring my broken Cantonese. It took me a while, but I realized I was speaking the wrong dialect even. Most spoke Sze Yup, with roots in Toisan or Hoi Ping provinces. Thankfully, standing up for your rights is a universal language.

When I worked in larger shops unionized by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, workers were divided by race. The union officers who were White and African American had little understanding toward the immigrant Chinese women and didn’t try to break these barriers. In mandatory union hall meetings, the president Mattie Jackson would talk on and on in English, making no attempt to address the Chinese-speaking majority who couldn’t understand a word she said. As the first African American woman to hold the position, she had a loyal base within the pre-1965 era White and Black garment workers. Mattie wasn’t interested in defying the ILGWU’s conservative national leadership. ILGWU was in fact waging a BUY AMERICA campaign with patriotic fervor against cheaper imported goods from Asia and Latin America, ignoring the growing trend of American manufacturers themselves running away to overseas factories. ILGWU hierarchy couldn’t relate to a non-European immigrant workforce.

But things in the union began changing when 100 Chinatown garment workers went on strike to unionize. Their shop Great American Sewing Factory, or Jung Sai in Cantonese, was located right around the corner from ACC and the I-Hotel. Two of the Co-op workers had gone there to work after the Co-op closed. They suggested going to the young people in ACC for support. The factory was owned by Doug Thompkins who also owned Espirit de Corp, a popular fashion brand. The Jung Sai strikers came down to ACC to ask for assistance after the entire workforce was locked out from the factory for union activity.

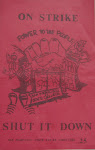

While the Jung Sai women were fighting for an ILGWU union contract, there was a good number of them who were not about to follow the unions strategy of calling off their picket lines and waiting for Doug to come around to signing a contract. JUNG SAI MEANS FIGHT BACK became their battle cry. All of Chinatown, even the conservative associations and newspapers became supporters of the strike. Mattie Jackson counted on the language barrier to give her unchallenged control. Now she was faced with a group that wanted translations and wanted a say in decisions. They had been locked out from their jobs and they weren’t about to disappear peacefully. They voted to take their picket line to the Espirit headquarters and stop the delivery trucks. This led to twelve being arrested, including myself and another woman from ACC. To our increasing admiration, the Jung Sai women went to jail in the patty wagon, singing and chanting all the way through booking, fingerprinting, and being locked behind bars. They kept it up until their release a few hours later.

I got married between picketing at the Jung Sai strike. I bought a new dress and we went down to City Hall to a judge’s chambers for the ceremony. Immediately after tying the knot, my husband and I ran back to join the picket line again. The Jung Sai workers congratulated us and then teased me mercilessly. To my embarrassment, I had bought a scab dresses from Macy’s in my hurry to get a wedding outfit. The strikers immediately recognized it as one of the styles they had sewn.

While waiting for a NLRB back wages decision, Jackson refused to let the strikers attend the Local 101 membership meeting when they tried to bring their plight before the local members. This insult to the strikers was not unnoticed by the other union members. Why didn’t they have the right to attend the meeting? Weren’t they fighting for workers rights? In the Local 101 meetings, the Chinese women began asking those who spoke English to interrupt the agenda, and speak about their working conditions. Then they began demanding a Chinese translator for the meetings. It was a rebellion among the members for union democracy. Mattie had to relent and provide a union translator for every membership meeting.

When executive board elections came up, myself and another ACC member were elected by the union members to represent them on the board. The National ILGWU leadership was alerted. As executive board members we participated in the next ILGWU S.F. contract negotiation. Having us at the negotiations was painful for the officials. Then on top of that, we brought STOP RUNAWAY SHOPS picket signs to an ILGWU Buy America Campaign rally. The ILGWU National campaign avoided blaming employers running away overseas for the growing layoffs. With a plan to get us out of the executive board, the union officials took photo evidence of us holding these rank and file signs. In closed session without the consent of the members, the ILGWU officials brought charges against the two of us and accused us of not only being part of a rank and file movement, but also of being communists. It was like we were before Joe McCarthy and the 1950’s House of Un-American Activities trials. Using an old statute from the 1930’s purge of union communists, we were expelled from the executive board by a kangaroo court of Mattie’s officers.

I left the garment factories after having two more children during those years. As you can guess, I was eventually fired. The factory I worked for later closed and laid off its hundreds of workers. Since then, the majority of U.S. clothing manufacturers did run away and are contracting overseas where unprotected labor is cheaper.

Thirty years past, hopefully today’s ILGWU has a more progressive leadership. And today, worker centers like ACC, AIWA and many more, continue forming and have become important organizing bases for new generations of immigrant garment workers.