I was invited to write down some of my memories of my involvement as a woman in the Asian American Movement. I decided to do it because there is so little written about the Asian Community Center and Wei Min She (Organization for the People) both of which were an important part of the leftist movement in San Francisco Chinatown and the Bay Area during that time period.

“Women’s Oppression Impacted My Life”

Women's oppression had a big impact on how I developed as a person. I wasn’t conscious of it at the time. And in fact, when I first heard the term “women’s oppression”, I didn’t think it applied to me. How am I oppressed as a woman? “I was free to be and do what I wanted” was the belief I had. In 1970 I went to one of the first Women’s Day celebrations in the Bay Area. But I did not fully grasp at that time how important it was to take on the women’s question. Only now, looking back, women’s oppression should have been one of the initial causes of why I became involved with the radical movement in the 1970’s. Also, it was my own experience of women's oppression that is behind the reason why I never had the confidence to step forward to make even more of a difference during that time of widespread turmoil and activism.

I not only did not see myself as a leader, but also shied away from that role. One of the most vivid examples of this was during a trip to Canada in the early 70’s to attend a Women’s Conference that presented women speakers from Vietnam. This was an important international conference to build opposition to the Vietnam War and expose the atrocities that were being committed by the U.S. military. There was a bus load of women from the San Francisco Bay Area and other West coast cities that went to the conference. For the final day of the conference, the women voted for a representative to read a statement that would put forward their stand with the struggle of the Vietnamese people and oppose imperialism. I got the most votes because I was a member of the respected Wei Min She organization. But I was too timid to speak in front of an audience and declined, letting the second runner-up take my place. Even a woman from I Wor Kuen tried to struggle with me to do it, since I would also represent the Asians from the U.S. who were there (the runner-up was not Asian.) Needless to say, people from Wei Min She were not happy with me when I got back. Not being proud of my action, I avoided speaking about my trip to Canada even though it was such an important event. But I think my bringing it up here, in the context of talking about women's oppression, makes a good illustration of how oppression can suppress a person, preventing the full development of an individual's abilities and as a contributing member of a society or cause.

Women’s oppression impacted my life. It also impacted my life through how it influenced my mother’s life.

My mother came to the United States on a boat from China at the age of 22, just married to my father, and pregnant with her first child. My father had gone to China after World War II under the War Brides Act. On arriving in China, my father was introduced to two young women, and of the two, he picked my mother to marry him. She would have two more pregnancies after that, each one year apart. The third one was me. So here she was, in a new country, couldn’t speak the language, with very little money, and three babies. What a scary situation. My father wasn't around much in those days since he was going to school on the GI Bill and working at night at various jobs such as janitor or washing dishes and cleaning up at restaurants.

Fortunately, she didn’t get pregnant again for another three years after that. But all the stress of having and taking care of three little babies must have been tremendous. This was quite common in Chinatown back in the 1950’s. People had big families back then. My mother ended up having a total of six children.

So this was the situation into which I was born. And from the very beginning was a disadvantage. I was the third child my mother gave birth to within three years. All three were born in the month of August, one year after the other. Looking back, after I took courses in Chinese Medicine, it became clear why my health was never very good. According to Chinese Medicine, after giving birth, a woman’s body becomes depleted of qi, blood, and other substances and needs to recuperate. A two or three year gap between children would be better for the health of the mother and children. But this is not what happens in real life. As a result, I was never very strong and had headaches all my life due in part to my mother having three pregnancies within too short a time period. A woman who is over-worked and depleted will not have enough qi and other vital substances to pass on to the next child for optimum health. Thanks to the women’s movement, women now have more control over reproduction, but there is the continuing struggle to keep the right for women to choose from being chipped away.

Another disadvantage was that I was born a girl into a Chinese family with traditional views on the value and role of women. Even though my father was politically progressive, both my parents placed more value on having boys over girls. This outlook was very typical of my parents' generation, much less of the many generations before theirs who lived under feudalism in China. I remember going out in Chinatown, when I was a little girl, and hear how some mothers would scold and call their daughters awful names. My mother used to point out how lucky I was that she didn't use those types of words on me. While my parents wanted me to have good grades in school, they didn’t expect me to go to a four year college like my brothers. What a shock it was to hear my father’s response to my applying to be admitted to S.F. State College. "Why would you want to do that?" my father asked me. He thought a two-year college was all I would need. Why waste the money? To lessen the pain I felt from his response, I excused him for it by being understanding of the financial pressure he was under, having four sons he wanted to put through college.

My mother’s treatment of me has never been very good because I was not a boy. I tried to explain this to my oldest brother a few times when we were adults, and he never believed me until one day he saw it for himself. My mother made soup for the family, and there were a number of bowls filled with soup on the table. I went over to get one and my mother said “No, those are for your brothers, go get your own.” My brother looked at me, and I said, ”See what I mean?” He understood then what I had been talking about. I was a second class citizen in my own family. It was unfair to be treated this way, but I understand that it was due to a cultural outlook that my parents grew up with in China. This was part of women’s oppression in Chinese traditional culture. Women were considered inferior to men, and women's role was to serve the men in the family. My mother was never able to break from this view of her role, and it is sad for me to see how much her interests in life is limited to the family. Mao’s China took on this oppression, liberating the women of China from this feudal outlook and even influencing the development of the women’s movement in the U.S. as well. Unfortunately, some of these gains for women in China were reversed after Mao’s death as the succeeding leaders in China embraced capitalism.

“I’m Going Too”

The 1960's was a time of social turmoil, both internationally and within the U.S. Countries in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America were fighting for freedom from colonialism. In the U.S. people were marching and demonstrating for civil rights and the right of Blacks to vote and ending Jim Crow laws in the South. There was the Free Speech Movement on college campuses. There was the start of the Vietnam war and the anti-war movement. With the start of the Black Power movement, similar movements arose in the Latino, Native American, and Asian communities. Militant groups like the Black Panther Party and Brown Berets developed across the country. San Francisco State College (now university) was one of the hot spots for the Free Speech Movement and the site of many demonstrations.

In 1968, I was 18 years old and it was my first semester at S.F. State. That semester, the first Third World Strike broke out. Among the demands were that education should be relevant to the community. That college education should be made accessible for minorities and the poor. That colleges and education should not be geared to the interests of making profits for the corporations and the military-industrial-complex. There should be ethnic studies so minorities could know their own histories and learn how to be of service to their communities. This was my start in becoming active in S.F. Chinatown and the Asian American Movement. It was here that I walked my first picket line and signed up to tutor immigrant school children in Chinatown. But the leaders of the strike did not reach out to involve me further and I was too shy to approach them myself. My further involvement would come from another direction.

Since junior high school (now called middle school) I was pretty much a book-reading recluse. I would borrow books from the public library and read on many subjects, fiction and non-fiction. In particular, I read as much science fiction as I could find. My particular heroes back then included astronomers Copernicus and Galileo and physicist Marie Curie. My two older brothers were more socially active. They went to Boy Scouts, drum and bugle corps, joined a kung fu club on Jackson Street, and played sports with friends. I was not into joining in with these types of activities. All my time was spent going to school, reading, and studying in my room at home. But this was going to change. Around 1968 I heard my brothers talking about going to Leeway, a pool hall for youth, where there were people talking about Mao Tse-tung, the Black Panther Party and reading from Mao's Little Red Book. This was where the Red Guard Party would form. Later on, my brothers would bring one of the founders of the Red Guard Party, Alex Hing, to our home to meet our father. The Red Guard Party wanted someone to translate their leaflets into Chinese. My father agreed to help.

The Red Guard Party was modeled after the Black Panther Party. They recruited mainly street kids as members. My father was very progressive in his politics. He was against the war in Vietnam, supported revolutionary China, and was persecuted during the McCarthy era by the FBI for being a member of Mun Ching, a progressive youth organiztion in Chinatown that had disbanded in 1959 when they lost their club house. The government carried out their anti-communist investigation into the Chinese community for many years begining in 1949 with the birth of New China under Mao. One angle to attack the left and progressives in Chinatown was through how many Chinese immigrated to the U.S. During the years when the Chinese Exclusion Act was still in force, many Chinese came to the U.S. illegally as "paper sons." My father was harassed for years, and when a cousin of his "talked", it opened the door for the FBI to act. My father's citizenship was taken away even though he had joined the U.S. army to fight against fascism in World War II. He would have been deported to China except for the fact that the U.S. couldn’t deport him to a country they didn’t recognize. I remember my father's response to losing his citizenship, he said that it's alright because he would rather be "a citizen of the world." So my father had been politically active when he was a young man, and after the Black Pather Party formed in the Bay Area, he used to bring home copies of the Black Panther newspaper that he bought on the street. So it was no surprise that he would help translate for the Red Guards. My father would later also translate material for the Asian Community Center and Wei Min Newspaper. I was proud of him for his hard work. He would go to work all day, and when he came home, he would stay up late to do the translations. He continued to do this even after he had a heart attack.

When the Red Guards started a free breakfast program like the Black Panthers, I volunteered to help during the summer of 1969. It was run out of one of the clubs on Broadway Street. But my long term involvement in Chinatown as an activist would not be with the Red Guards, but with a group of students from Berkeley who would set up the Asian Community Center and Everybody’s Bookstore at the end of 1969.

I didn’t know these students from Berkeley since I went to S.F. State. But both my older brothers went to U.C. Berkeley and they got pulled into action like many others. Berkeley had a history of student activism on campus. In the late 60’s Berkeley really heated up with protests. There were teach-ins on the Vietnam War, anti-draft actions, the Third World Strike, People’s Park. In response, the national guards were sent in with tear gas and even fired shots into crowds. The first time I saw some of these Berkeley students was in a huge anti-war protest in 1969 that marched from downtown San Francisco to Golden Gate Park. My brothers were going to the march with a friend. When I said, “I’m going too.” they didn’t object and I went too.

There had been many demonstrations against the war in Vietnam and now I was in one myself. My family was against the war but had never taken part in protest before. Now I was actually in one. It was very exciting with so many people. Along the way, we came across the Asian Contingent and marched with it. They had their own banners and signs. They raised opposition to the war from an Asian perspective, one I never thought about before. They said the Vietnamese people were our brothers and sisters. That the U.S. military called the Vietnamese “gooks," and that was how the military saw all Asians. I was amazed that some of them spoke Chinese, in fact they spoke Sze Yup like my family did at home, and not Sam Yup (Cantonese). As the march approached Golden Gate Park, we saw some Black Panther Party members passing out pamphlets by Mao tse-tung and selling their newspaper. We stayed to hear speeches and finally had to leave since we had nothing to eat or drink.

Surrounded By Banned Books

One day my oldest brother was talking about how he and a number of other students at Berkeley had chipped in $50.00 each to open a bookstore. At the mention of “bookstore” I immediately said I want to go there to work. I loved to read and had always wanted to work in a bookstore or library and be surrounded by books. He said he would find out for me and that was how I ended going to Kearny Street where I attended my first meeting. I was quite shocked when I was asked to give my opinion. As I mentioned, I was pretty reclusive and did not talk much.

The meeting was held in the basement of the building next to the International Hotel, at what was once the United Filipino Association Hall, 832 Kearny St. This would be the first location of the Asian Community Center. Later, we would be evicted and we moved into one of the basements in the I-Hotel at 846 Kearny Street. The bookstore was named Everybody's Bookstore and was in a storefront in the I-Hotel. Staffing for ACC and the Bookstore would all be done by volunteers, there was no money to pay for staff. Originally, the Bookstore was in a very small space, the size of a room in a house. It had very few books in the beginning, some were in English and some in Chinese. Many of the pamphlets and books were from China. The source of the books was probably China Books. I wasn’t involved with buying books for the store, but there was only one possible source for books like Mao’s red book and other writings.

China Books was the only importer for books, posters, and records from China in our area. I had gone to China Books before with my father and a number of his friends who used to be Mun Ching members. It was considered subversive to go to China Books because it imported goods from the People’s Republic of China, which was not recognized by the U.S. government. The China the U.S. recognized was Chiang Kai-shek’s Republic of China located on the island of Taiwan. Chiang Kai-shek and the political party he led, the KuoMinTang had fled to Taiwan after the victory of Mao Tse-tung’s revolution in 1949. In fact Chinatown back then was polarized along the lines of supporting Mao’s communist China and Chiang’s KMT Taiwan. Back in the 1950’s when Mun Ching had their club house on Stockton Street, the KMT used to throw garbage in their doorway. Mun Ching had members who supported the People's Republic of China so they were accused of being "communist." So I remember I had gone to China Books with my father, and I was shown books that were stamped by custom officials with words indicating the material was “banned”. I didn’t quite understand the politics and what it meant at the time since I was young.

My second brother didn’t get involved in ACC. He worked with the International Hotel for a while and often hung around with two I-Hotel women friends. My mother was quite upset when he brought them home a few times, one friend holding his arm for a guide as she was blind. I had a good laugh over her disaproval. I think my mother was also upset that I started to get active and leave the house. "Mh nah ga!" - which meant "never staying home."

“What We Want. What We See. What We Believe”

The first time I went down the stairs to the basement was in December 1969. People were watching revolutionary movies and newsreels. The free community film showings was one of the first programs the Berkeley students set up. The newsreels were documentary shorts on things like the Black Panther Party. They showed movies like “Battle of Algiers” which depicted how the Algerian people organized to fight for liberation from the French. The film program was one of the ways to educate the people to become political and class conscious so they could organize themselves to change society. After ACC was officially formed in 1970, I would soon learn to run the projector myself, and help set up weekend movie shows. We often showed movies about revolution and films from China showing the struggle for socialism that came from sources in Canada, since Canada did have relations with China. I will never forget the time we showed "East is Red," a song and dance drama of the Chinese Revolution, one weekend. We showed it for a total of fourteen times and it was packed for each showing. There was so much emotional response from the audience. During one afternoon showing, when it came to a scene of a woman forced to sell her daughter in the movie, a woman in the audience started sobbing loudly. It was too dark to see who it was, but we wondered if something similar had happened in her family.

In the early days, many of the regulars who came down to the basement were elderly men. Later, people of all ages would come down, including grade-school children. Due to exclusion laws against the Chinese, many of the early immigrants could not bring family members to the U.S. The men grew old all alone, working here and sending money home to families in China. ACC became the daily hang out for many of these old men. Some supported Mao and China for the politics, and some out of pride seeing their home country strong. I spent much of my time in the 70's at ACC. At school, when I got involved going to meeings to discuss the very beginnings of the Asian American Studies program and the Asian Women's class, I was seen as someone coming from ACC.

At the Asian Community Center, we had meetings to discuss the center's aims and purpose. Many groups in those days had a program. The Black Panther Party had their Ten Point program. We wanted something of our own. After discussing the issues that plagued Chinatown such as the highest TB rate in the country, crowded living conditions, sweat shops and restaurants with low paying jobs, long working hours, we came up with “What We Want. What We See. What We Believe.”

WHAT WE SEE

We see the breakdown of our community and families.

We see our people suffering from malnutrition, tuberculosis, and high suicide rates.

We see the destruction of our cultural pride.

We see our elders forgotten and alone.

We see our Mothers and Fathers forced into meaningless jobs to make a living.

We see American society preventing us from fulfilling our needs.

WHAT WE WANT

We want adequate housing, medical care, employment, and education.

WHAT WE BELIEVE

To solve our community problems, all Asian people must work together.

Our people must be educated to move collectively for direct action.

We will employ any effective means that our people see necessary.

I learned a lot about radical politics in these meetings. One thing the Berkeley students raised was how to work together. We were going to work collectively. Everyone would have input on decisions. Another thing we decided was that we were going to base ACC on the working class, not the lumpen proletariat (street people) like the Black Panthers or the Red Guards. It was here that I became aware of different political lines between groups. People who had similar lines would be able to come together and do work, whereas people with different lines would not. The original group of students who formed ACC were all American born but was able to join with a group of Hong Kong born students shortly after. Later Wei Min She was formed as an organization to lead the work politically.

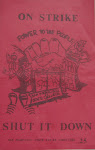

Eventually we started many “serve the people” programs such as: weekly film showings; the Food Program where we distributed government supplemental foods to pregnant women and young children; we put out a family newsletter; in the summer we had a Summer Youth Program for school age children with tutoring and field trips. We set up health screenings for TB and glaucoma for the community at ACC soon after we formed, and later helped organize health fairs with other Chinatown organizations at Portsmouth Square, the park located a block from the center. We took on housing issues such as improving conditions at the Ping Yuen housing projects in Chinatown and the International Hotel. We supported worker's struggles at restaurants, garment shops, and electronic factories.

There was so many areas of work that special work groups were set up at different times. There was labor, health, education, housing, the newspaper Wei Min Bao, the Bookstore, etc. We also set up study groups to carry out political education for ourselves and for the volunteers who were interested in working with us. We studied the writings of Mao Tse-tung and applied much of it to our work. We studied the current conditions in the world, in the U.S. and in Chinatown. We went out to the masses to investigate their situation and get their opinions. We tried to apply criticism and self-criticism as we summed up our work. We studied the writings of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and books on the revolution in China such as Edgar Snow's "Red Star Over China." We read the writings of Malcolm X, Che Guevara, Frantz Fanon and many others in search of the direction forward for revolutionary change. We set up classes to study the "the women's question," and "the national question." In the summer of 1971, historian Him Mark Lai gave a series of six lectures on "Chinese in America" at ACC.

ACC and Everybody’s Bookstore was also a part of a larger Kearny Street community. There was what was left of Manilatown, reduced from ten blocks to just the I Hotel, the barbershop, Mabuhay Restaurant and the pool hall across the street. There was the International Hotel’s fight against eviction which drew many people from the community and students from campuses to join in the struggle. There were various other organizations that rented space in the I Hotel throughout the 70's including Draft Help, the Garment Co-op, the Red Guard Party, Chinese Progressive Association, I Wor Kuen, and Kearny Street Workshop.

This period of time in my life was rich with experience and people. I learned to do things I never dreamed of doing before including leading group meetings and discussions. I changed from being timid to a community activist on the streets of Chinatown, selling newspapers, passing out flyers, and talking to people on the various issues we took up. We had such hopes then of revolution, of changing the world and all of the existing social relationships. We wanted a world without exploitation and oppression. Looking at the world now, there is still so much more work to be done.

A Wei Min Sister