|

| Oakland High School students participate in funeral for Black Panther Bobby Hutton, killed by Oakland Police in 1968. (Photographer: Nikki Arai, 1968) |

Sunday, January 20, 2008

Introduction to the Asian American Movement 1968

The Sixties and Seventies, I mean.

You had to be there, sensing the world turning upside down.

It wasn't remote or academic at all.

On our TVs and in our newspapers we witnessed Asian faces rising up to finish off the latest colonial occupation.

once dismissed as clinging to a colorful past

while waiting for some foreign missionary power to take it under its protection,

had now stood up,

an enormous Red banner of self-determination.

Every American guy graduating high school stared right into the gun barrel of the military draft

and had to decide for himself what the world was about

and where he stood in it.

Political assassinations that shocked the nation and sparked frightening riots happened right here in our own cities.

There was no irony in a militant Black Power salute

or a gentle wave of "Peace, man".

It was real.

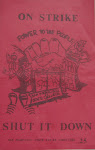

Then, as now, oppression breeds resistance. In the spirit of those tumultuous times, we present this collection. From these stories, old photos and artifacts we see stepping stones being laid down for advancing the peoples' causes still being fought. Our corner of the world was the San Francisco Bay Area and we begin in 1968.

Asian Community Center History Group Project

The Asian Community Center History Group put together this collection of reprinted newspaper articles, mimeographed pamphlets and black and white photographs from the period. We hope to document this unique movement by letting the reader peruse the original writings and concerns of that time. Our collection was donated from the personal keepsakes of many individuals who saved the materials for forty years, preserving their collections for historical value. The contents of the reprinted materials have been duplicated for the reader. Where possible, the original pieces were digitized for viewing as well. Understandably, the majority of the content is about the development of the Asian Community Center Kearny Street

The project also reprinted a few articles from the Japanese American movement newspapers to bring attention to the important struggles in Japantown, though these organizations were not affiliated with ACC.

Other sources of reprints are from the Berkeley Barb, San Francisco Journal, Kalayaan, Red Guard Bulletin, Getting Together, New Dawn, Rodan newspapers. We've included these and other unaffiliated sources in order to give the reader a sampling of the wide range of voices during the period.

We hope that the material will be useful for those who were touched by this era and wish to examine more in depth its significance. And we hope that new generations can find value in examining the past to serve the present.

A History of the Asian American Movement

The Asian American movement began in the late 1960s and early 1970s during one of the most tumultuous eras in post-WW2 history. In the Bay Area, the Year 1968 marked a wave of Asian American activity. Three distinct Bay Area events earmarked the beginning of this local movement.

1. The 1968 formation of the Asian American Political Alliance in Berkeley

2. The 1968 San Francisco State University

3. The International Hotel tenants’ first eviction notice in December 1968.

The Asian American movement began amidst national and worldwide turmoil. The Vietnam War, the Civil Rights and the Black Power movements were major factors in profoundly influencing large numbers of Asian Americans to question the nature of American democracy. Revolutions throughout the underdeveloped Third World, and China Berkeley

Asian American Political Alliance

In 1968, Asian American civil rights and anti-war activists turned their attention to the specific needs of the Asian American population in the U.S. Berkeley

The term “Asian American” became a unifying force among the different Asian ethnic groups. AAPA helped open an avenue of activism for many Asian Americans who later took part in the social transformations of the period, including the Third World Liberation Front Strikes at San Francisco State University (SFSU) and University of California Berkeley U.S. as well, including Los Angeles , New York , and Hawaii

The formation of the Third World Liberation Fronts in San Francisco and Berkeley

International Hotel Fight Against Eviction and Community Struggles

Shortly after the period of organizing students to struggle for the establishment of various Asian American Studies programs on the college campuses, student activism extended into the surrounding communities. This took the form of establishing community centers and organizations that focused on “Serve the people” programs. In the San Francisco Bay Area, Asian American activists opened a number of centers. In San Francisco

Much different from campus life, community activism addressed the local needs and conditions of the Asian American communities. As the movement became grounded in local conditions, grassroots leadership and participation grew.

A pivotal point for the Bay Area Asian American movement was the struggle against the eviction of the International Hotel tenants in San Francisco Chinatown . But within this local background were multiple levels of power that represented globalization—in the form of Bay Area Regional master plans and Pacific Rim development. These forces had already destroyed most of Manilatown and were eliminating many existing housing units in the adjoining Chinatown (mostly bachelor hotel rooms), replacing them with office high-rise buildings, hotels, and retail spaces.

Similarly, redevelopment-related issues were focal points of protest in other Asian American communities. In S.F. Japantown, the Committee Against Nihonmachi Evictions (CANE), consisting of the J-Town Collective and community individuals, emerged to address the needs of residents and small businesses. CANE became involved in supporting low-income affordable housing issues and protests against destruction of residential and small business districts. It had a membership base of over 300 residents who were discontented over the direction of the redevelopment largely owned by Japanese multinational corporations.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment